Neurodivergent Voices

Dear Dr. Pearl

Getting an accurate Autism or ADHD assessment can be challenging if you don’t fit into diagnostic boxes that are based on the observable behaviour of young boys. These boxes don’t even fit all boys or men, let alone girls, women, non-binary, or trans individuals. This article is written by a self-diagnosed Autistic female-presenting person in the form of a letter to the psychiatrist who found her too ‘high-functioning’ to be on the Autism spectrum and is the first in our series of neurodivergent voices. Jesse just finished their BSW placement at Scattergram and is now a member of the practice as Intake Worker and Registered Social Worker.

Dear Dr. Pearl,

Imagine going through life never being believed by anyone, your experiences undermined because you don’t fit into a particular mold– this is the Autistic experience.

As a child, I was in perpetual confusion in most social interactions and found comfort in the objects I collected and the imaginary worlds I would create through art. At home, I would have meltdowns from sensory overstimulation and be told that I was “overreacting” even though the itching in my head felt real. At school, I was bullied and taken advantage of by my peers and by adults who were supposed to be my caretakers and educators.

I wholeheartedly believed I deserved poor treatment for my perceived social “deficiencies” at a young age. I would consciously think about making eye contact because it seemed important to show respect. I would catch myself assessing the most appropriate body language to use in mid-conversation; researching the meaning of nonverbal cues post-interaction. I would prep scripts to anticipate multiple conversational outcomes based on potential scenarios.

“…when an Autistic person seeks clinical validation…after years of being considered deficient as a neurotypical, it is a reclamation of self.”

Socializing “correctly” (or at least neurotypically) was an elaborate performance that I perfected to avoid being ostracized through close observation of myself and others; this was not always successful and I would lose friends without understanding why. Even sitting down in a classroom and opening my textbook was intellectualized, right down to how many seats were acceptable to leave empty between my classmates and me.

All of my reactions to the world around me were chosen based on the logical conclusions I came to. At times I don’t even recognize myself as I become an amalgamation of media and peers blended to form a persona. After a while, the mask falls, and I shut down, throwing my entire life off balance for months at a time which is assumed to be a random bout of laziness or depression. A lifelong pattern follows and all of these experiences have been disbelieved in a few hours by a qualified stranger. I guess my acting was too good because I fooled you into believing I was “neurotypical enough” to get by.

Imagine if it were you, Dr. Pearl, on a 2-year waitlist for Ontario’s government-funded Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) assessment after receiving a referral from your doctor for a diagnosis that has contextualized many of your lifelong experiences, effectively encapsulating it in one word: “Autism”. Imagine the lengthy interview process with you as the one relaying your life story, sometimes with your parents watching. Imagine what you would think and feel as you completed the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) at the age of twenty-six, a questionnaire designed for children.

“…my awareness of the assessment and desire to perform it “correctly” likely backfired on me…”

For me, it seemed like there was an underlying secret method of engaging (or not) with the toys strewn before me on the table that I needed to figure out. None of the objects particularly interested me and I would not usually interact with them by choice. Still, because I knew you were observing me, I picked up each toy and acted curious (emphasis on ‘acted’). I reflect now that my awareness of the assessment and desire to perform it “correctly” likely backfired on me because you drew the conclusion that I appeared too “high functioning” to be Autistic. I have friends, I can verbally articulate myself, have “normal” affect, and balance work and school.

You seemed to be looking for reasons for me not to be Autistic rather than trying to understand me. You wanted to confirm the falsities of my claims based on observable behaviours that had nothing to do with my internal experience and lifelong challenges that I painfully overcame by myself. There was no nuance in your examination, only surface-level and highly stigmatizing assumptions and age-inappropriate assessment tools that assume Autistic people to be incapable of coping and adapting to their environment.

“I am neither Autistic nor neurotypical enough.”

I have come to learn that there is shame in my natural tendency to hand flap, run on tip-toes and make incoherent vocalizations. That my sensory difficulties are either fake or “me being dramatic.” I have been told that my constant social confusion and scripting of every scenario is only social anxiety, even when I genuinely do not feel anxious. People tell me what I am experiencing and it is difficult to know what is reality. I am told that I am to blame for the shortcomings of my environment in accommodating my needs and the social intolerance towards neurodivergent traits. I am also to blame for being too good at pretending to be “okay” and “normal”. I am neither Autistic nor neurotypical enough.

When you are constantly socially rejected and the people around you make assumptions about who you are, that becomes your reality and beliefs. And then you lose your sense of self and are shaped by those labels people determine for you. So when an Autistic person seeks clinical validation (because Autism is still widely regarded as a neurological disorder) after years of being considered deficient as a neurotypical, it is a reclamation of self. It is realizing that you are okay as you are, that you are doing what is natural for you to survive. When someone takes that from you, it can ruin that sense of self-concept and force you back to square one. We should not be pathologizing one’s neurotype based on how well they function and cope with an environment not designed for them. But if a diagnosis makes someone feel seen, heard, and understood, with the potential to access resources they might need, then that should be a well-supported cause to change our way of diagnosing people (diagnostic tools and processes).

“I want you and your colleagues who have the power to diagnose someone to understand how imperative it is to set aside your own biases and try to see the person, to see past what they superficially present to you, to see their internal world.”

I am writing this letter to call attention to the necessity for improved diagnostic tools for adults that exceed the rigid criteria of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V) that only recognize a narrow assortment of male-centric phenotypic traits, disregarding the nuance of masking. This is especially true for those who are raised as women but is relevant for all genders.

Dr. Pearl, I want you and your colleagues who have the power to diagnose someone to understand how imperative it is to set aside your own biases and try to see the person, to see past what they superficially present to you, to see their internal world. Understand why we seek a formal diagnosis and what type of support we are looking for. On top of that, adults should not be assessed based on unreliable childhood recollections of their caregivers. Not only does this requirement prevent some people from accessing a diagnosis if they are estranged from those caregivers, but it also solidifies the assumption that Autism is only a childhood developmental disability, which is objectively false. Autism is someone’s neurological lifelong makeup. You can’t change that, no matter how much you mask and try to manage your behaviours as an adult. You are born Autistic and you are always Autistic, it is not something that can be “cured” nor should it be. That fact alone needs to be accepted.

Signed,

Jesse Smith, 27, self-diagnosed Autistic person

Is this similar to your experience or have you avoided assessment for fear of invalidation? Do you want to reclaim your identity from years of invalidation through a clinical diagnosis?

Explore these articles and resources:

Not Sure if You’re Neurodivergent?

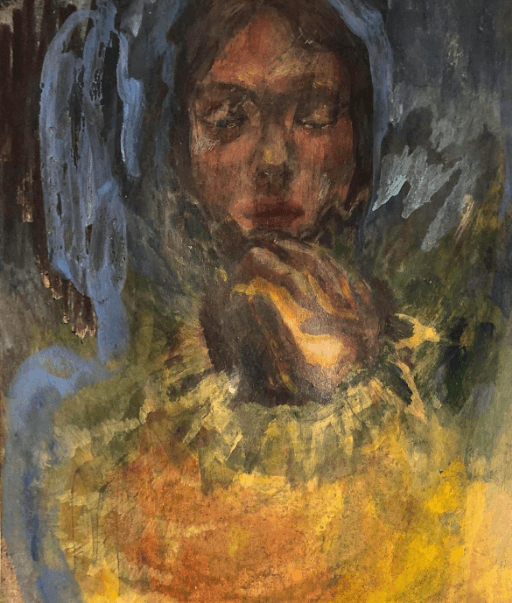

Artwork by Jesse (link opens in a new window)

If you’re ready to take that first step to talk to someone about your neurodivergence, whether you are self-diagnosed, late diagnosed, or still a big question mark, reach out to one of our Psychotherapists.